Benjamin Huger (general)

Benjamin Huger | |

|---|---|

Major General Benjamin Huger, CSA | |

| Born | November 22, 1805 Charleston, South Carolina |

| Died | December 7, 1877 (aged 72) Charleston, South Carolina |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1825–61 (USA) 1861–65 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 3rd U.S. Artillery |

| Commands held | Department of Norfolk Huger's Division |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

| Signature | |

Benjamin Huger (November 22, 1805 – December 7, 1877) was a regular officer in the United States Army, who served with distinction as chief of ordnance in the Mexican–American War and in the American Civil War, as a Confederate general. He notably surrendered Roanoke Island and then the rest of the Norfolk, Virginia shipyards, attracting criticism for allowing valuable equipment to be captured. At Seven Pines, he was blamed by General James Longstreet for impeding the Confederate attack and was transferred to an administrative post after a lackluster performance in the Seven Days Battles.

Early life and U.S. Army career[edit]

Huger was born in 1805 in Charleston, South Carolina. (He pronounced his name /juːˈʒeɪ/, although today many Charlestonians say /ˈjuːdʒi/.) He was a son of Francis Kinloch Huger[1] and his wife Harriet Lucas Pinckney, making him a grandson of Maj. Gen. Thomas Pinckney.[2] His paternal grandfather, also named Benjamin Huger, was a patriot in the American Revolution, killed at Charleston during the British occupation.[3]

In 1821 Huger entered the United States Military Academy and graduated eighth out of 37 cadets four years later. On July 1, 1825, he was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant, then promoted to second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery on that same date.[4] He served as a topographical engineer until 1828 when he took a leave of absence from the Army to visit Europe from 1828 to 1830. He then was on recruiting duty, after which he served as part of Fort Trumbull's garrison in New London, Connecticut.[5] From 1832 to 1839 Huger commanded the Fortress Monroe arsenal located in Hampton, Virginia.[2]

On February 7, 1831, Huger married his first cousin, Elizabeth Celestine Pinckney. They would have five children together; Benjamin, Eustis, Francis, Thomas, and Celestine Pinckney. One of his sons, Francis (Frank) Kinloch Huger, also attended West Point and graduated in 1860. Frank Huger would enter the Confederate forces during the American Civil War as well, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel and leading a battalion of field artillery by the end of the conflict.[6] On May 30, 1832, Huger was transferred to the Army's ordnance department with the rank of captain; he would spend the rest of his U.S. Army career with this branch.[4] From 1839 to 1846, he served as a member of the U.S. Army Ordnance Board, and from 1840 to 1841, he was on official duty in Europe.[7] Huger again commanded the Fort Monroe Arsenal from 1841 to 1846, until hostilities began with Mexico.[5]

War with Mexico[edit]

Huger fought notably in 1846–48 during the Mexican–American War, serving as chief of ordnance on the staff of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott throughout the conflict. Huger commanded the siege train during the Siege of Veracruz, March 9–29, 1847. He was appointed to the rank of brevet major for his performance at the Veracruz on March 29 and to lieutenant colonel for the Battle of Molino del Rey on September 8. Huger was brevetted a colonel five days later for "gallant and meritorious conduct" during the storming of Chapultepec.[8]

Returning from Mexico, Huger was appointed to a board that created an instructional system for teaching artillery principles in the U.S. Army. From 1848 to 1851, he commanded the arsenal at Fort Monroe and then led the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia until 1854. In 1852, South Carolina presented Huger with a sword, commemorating his long and distinguished service to the state. From 1854 to 1860, Huger commanded the arsenal in Pikesville, Maryland, during which he was promoted to major as of February 15, 1855. Huger was sent to the Crimean War as an official foreign observer in 1856. Beginning in 1860, Huger commanded the Charleston Arsenal, holding the post until resigning in the spring of 1861.[9]

Civil War[edit]

Despite the declared secession of South Carolina in December 1860, Huger remained in the U.S. Army until after the Battle of Fort Sumter, resigning effective April 22, 1861. Just before the battle, Huger traveled to the fort and conferred with its commander, Maj. Robert Anderson, to determine where he stood. Although Anderson was also born in a slave state, he had already chosen to remain loyal to the United States, and Huger left when "their discussions came to naught."[10]

Huger was commissioned an infantry lieutenant colonel in the regular Confederate States Army on March 16, then briefly commanded the forces in and around Norfolk, Virginia. On May 22, he was appointed a brigadier general in the state's militia, and the next day took command of the Department of Norfolk, with defensive responsibilities for North Carolina and southern Virginia, with his headquarters located at Norfolk. Sometime that June, he was also commissioned a brigadier in the Virginia Provisional Army; however, Huger entered the Confederate volunteer forces on June 17 as a brigadier general. Later on October 7, he was promoted to the rank of major general.[11][12]

Roanoke Island and the loss of Norfolk[edit]

In early 1862, U.S. Army and Navy forces approached the North Carolina-Virginia coastline and Huger's area of responsibility. At Roanoke Island, his subordinate, Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise, asked Huger for various supplies, ammunition, field artillery, and most importantly, additional men, greatly fearing an attack on his quite unfinished defenses. Huger's response to Wise asked him to rely on "hard work and coolness among the troops you have, instead of more men." Eventually, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered Huger to send help to the Roanoke Island area, but it proved too late. On February 7–8, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough and his gunboats landed Brig. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's infantry, initiating the Battle of Roanoke Island. Huger, with about 13,000 soldiers, failed to reinforce the immediate commanders there, an ailing Wise and Col. H. M. Shaw, and Burnside quickly eliminated the Confederate resistance and forced a surrender.[13]

When news of the fall of Roanoke Island reached Norfolk's population, they quickly panicked, spreading the alarm to Richmond. Military historian Shelby Foote believed this loss "...shook whatever confidence the citizens had managed to retain in Huger, who was charged with their defense." On February 27, President Davis declared martial law in Norfolk and suspended the right of habeas corpus, attempting to regain control, and two days later, he did the same in Richmond.[14]

Due to the combination of the naval action at Elizabeth City on February 10, the Battle of New Bern on March 14, the Battle of South Mills on April 19, and other U.S. landings during the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate authorities determined Huger could not hold Norfolk. On April 27, he was ordered by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to abandon the area, salvaging from Gosport Navy Yard as much usable equipment as he could, and join the main army. On May 1, Huger began to evacuate his men and ordered the destruction by fire of the naval yards at Norfolk and nearby Portsmouth. Ten days later, U.S. forces occupied the Gosport Yards. Military historian Webb Garrison, Jr. believed Huger did not leave the area properly, stating: "...the evacuation of Norfolk was handled poorly by Confederate Gen. Benjamin Huger—too much property was left intact." Also lost as a result was the famous Ironclad warship CSS Virginia, scuttled by her crew when she could not stay in the James River, get past U.S. Navy forces at its mouth, nor survive at sea even if it did.[15] The United States would maintain control of the Norfolk facilities for the rest of the war, and the Confederate Congress soon began to investigate Huger's part in the defeat at Roanoke Island. He led his soldiers to Petersburg, where he remained until summoned by Johnston at the end of May.[16]

Peninsula Campaign[edit]

Confederate President Jefferson Davis assigned Huger to divisional command under Gen. Johnston within the Army of Northern Virginia. His command fell back with the main body as Johnston retired towards Richmond and then participated in the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31 and June 1, 1862.[17]

According to Johnston's battle plan, Huger's three brigades were placed under the command of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet as a support, but Huger was never notified. On June 1, as he moved his men toward the fight, their march was blocked by Longstreet's columns—who had taken an incorrect road—and halted. Huger found Longstreet, asked about the delay, and learned his role and the command relationship for the first time. Huger then asked whether he or Longstreet was the senior officer and was told that Longstreet was, which he accepted as true, although it was not.[18] This delay and Longstreet's instructions to stand by and wait for orders prevented Huger's division from supporting the advance on time and hampered the overall Confederate attack. In his official report of the Battle of Seven Pines, Longstreet unjustly blamed Huger for the less than entirely successful action, complaining of his tardiness on May 31 but not relating the reason for the delay.[19] In a private letter to an injured Johnston written on June 7, Longstreet stated:

The failure of complete success on Saturday [May 31] I attribute to the slow movements of Gen. Huger's command... I can't help but think that a display of his forces on the left flank of the enemy, by Gen. Huger, would have completed the affair... Slow men are a little out of place upon the field.[20]

Once he learned he had been criticized and blamed, Huger asked Johnston to investigate; however, this was refused. He then asked President Davis to order a court-martial, but, although approved, it never took place. Writing after the war, Edward Porter Alexander stated, referring to Huger, "Indeed, it is almost tragic the way in which he became the scapegoat of this occasion."[21]

The Seven Days[edit]

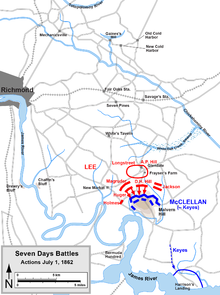

Huger then participated in several of the Seven Days Battles with the Army of Northern Virginia, now under the command of Gen. Robert E. Lee, who replaced the wounded Johnston on June 1. Lee planned an offensive against an isolated U.S. Army corps with the bulk of his army in late June, leaving less than 30,000 men in the Richmond trenches to defend the Confederate capital. This force consisted of the divisions of Maj. Gens. John B. Magruder, Theophilus H. Holmes, and Huger.[22] During the Battle of Oak Grove on June 25, his portion of the line was attacked by two divisions of the U.S. III Corps led by Brig. Gens. Joseph Hooker and Philip Kearny. When part of the assault faltered in rough terrain, Huger took advantage of the confused, uneven U.S. line and counterattacked with the brigade of Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright. After repulsing the charge, another U.S. force attacked Huger but was stopped short of the line. The Battle of Oak Grove cost Huger 541 men killed and wounded while inflicting 626 total casualties on the U.S. Army.[23]

Lee continued to order his army to pursue and destroy the U.S. forces. Following the action at Oak Grove, he pulled much of the defense around Richmond and added them to the chase, Huger's division included. On June 29, Magruder thought his position would be attacked by overwhelming numbers and asked for reinforcements. Lee sent two brigades from Huger's division in response with instructions they were to be returned at 2 p.m. if Magruder was not hit by then. The appointed hour came and passed, Huger's men were sent back, and later that day, Magruder "halfheartedly" fought the Battle of Savage's Station alone. Even without those two brigades, Huger was late in reaching his assigned position on June 29, countermarching needlessly and encamping his command without engaging with the enemy. The next day Huger was ordered toward Glendale but was delayed by the retreating U.S. forces who had cut trees to slow pursuit and the terrain that easily allowed for an ambush. Attempting to follow along the Charles City Road to his assignment, Huger had his men cut a new path through the woods with axes. This further slowed their advance while the other Confederate commands waited for his guns to fire, their signal to attack. Huger informed Lee of the delay by simply stating his march was "obstructed" without further description.[24]

Around 2 p.m., Huger's lead brigade under Brig. Gen. William Mahone cut a mile-long path around the U.S. obstacles, winning the so-called "battle of the axes", and continued to approach Glendale. There he saw the 6,000-man division of Brig. Gen. Henry W. Slocum arrayed to block his way. Huger ordered one of his artillery batteries to fire on this U.S. position at 2:30 p.m. but Slocum's guns answered quickly, and Huger led his 9,000 men off the road and into the woods after taking some casualties. Despite outnumbering the U.S. division, Huger made no further attempts to reach Glendale. However, his few artillery shots were interpreted by the other Confederates as the signal to attack, igniting the Battle of Glendale, although Huger and his command would not take part in the fight and camped.[25]

The following day, July 1, was Huger's last fight with the Army of Northern Virginia and his final field command in the American Civil War. His division was directed toward the U.S. forces on Malvern Hill without a definite target, as he was told that Lee would "place him where most needed" against the position. Because Magruder had mistakenly led his command away from the battle, Huger took up his place on the Confederate right, just north of the "Crew House", with the division of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill on his left. To give his infantry a chance to charge and break the U.S. line, Lee ordered a concentrated artillery barrage at Malvern Hill. One of Huger's brigades, led by Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, was to determine when this barrage had the desired effect and begin the assault. Before the cannonade could begin, the U.S. artillery fired first and took out most Confederate guns. Shortly after 2:30 p.m. Armistead went in anyway, and though his men made some progress, he failed to penetrate the strong defensive position. Other Confederate units made less progress and took heavy casualties, and around 4 p.m., Magruder arrived and put in two brigades—about a third of his command—behind Armistead, but he too retired with high loss.[26] Two more of Huger's brigades—led by Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright and Mahone, about 2,500 men—followed Armistead and toward Malvern Hill. Taking U.S. artillery and infantry fire as they advanced, Huger's men slowed and stopped, finding protection in a nearby bluff. They had fought to about 75 yards (69 m) of the U.S. line but could go no further. Huger's last brigade under Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom managed to get within 20 yards (18 m) by 6 p.m. but also fell back after receiving heavy casualties in the Confederate defeat.[27]

Following the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Gen. Lee began reorganizing his army and eliminating ineffective division commanders, including Huger. His actions since joining the army "left much to be desired", according to military biographer Ezra J. Warner.[28] Other historians have also criticized Huger throughout this time: Brendon A. Rehm summarized his battle performance as "not notably successful", and John C. Fredriksen stated Huger was "lethargic" during Seven Pines as well as moved "sluggishly" during the Seven Days fights. Furthermore, the Confederate Congress held Huger accountable for the defeat at Roanoke Island.[29] His dilatory performance also appears to have been blamed on his rather advanced age; at nearly 57, he was well above the average age of most field officers. As a result, Huger was relieved of command on July 12, 1862, along with Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes, another aging, ineffective division commander.[28] and that fall was ordered to serve in the Trans-Mississippi Department.[4]

Trans-Mississippi service[edit]

After the Seven Days Battles, Huger was assigned to be assistant Inspector General of artillery and ordnance for the Army of Northern Virginia. He held this post from his relief on June 12 until August, when he was sent to the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department. He was considered too old for field command and spent the remainder of the war in administrative duties. Huger was made the department's inspector of artillery and ordnance on August 26 and then was promoted to command of all ordnance within the department in July 1863. This position he held until the end of the American Civil War in 1865, when he surrendered along with Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith and the rest of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi forces. Huger was paroled from Shreveport, Louisiana, on June 12 of that same year, and returned to civilian life.[4]

Huger's Trans-Mississippi service in staff positions has been rated positively by historians. Ezra J. Warner believed this area of military service was "his proper sphere" and summarized Huger's overall performance: "These duties he energetically and faithfully discharged until the close of the war, most of the time in the Trans-Mississippi service."[28] Likewise John C. Fredriksen states, "He functioned capably in this office until 1863, when he rose to chief of ordnance in the Trans-Mississippi Department until the end of the war."[17]

Postbellum[edit]

After the war, Huger became a farmer in North Carolina and then in Fauquier County, Virginia, finally returning in poor health to his home in Charleston, South Carolina. He was also a member of Aztec Club of 1847, a social club formed just after the Mexican–American War by army officers. Huger served as its vice president from 1852 to 1867.[30] He died in Charleston in December 1877 and was buried at Green Mount Cemetery located in Baltimore, Maryland.[4]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger:' "His father, who was aide-de-camp to General Wilkinson in 1800, and adjutant-general in the war of 1812, suffered imprisonment in Austria for assisting in the liberation of Lafayette from the fortress of Olmutz..."

- ^ a b Dupuy, p. 354.

- ^ "Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger". ricehope.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Eicher, CW High Commands, p. 308.

- ^ a b "Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Huger". aztecclub.com. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger; Wakelyn, p. 241, gives a marriage date of February 17, 1831.

- ^ Wakelyn, pp. 241-42; Dupuy, p. 354.

- ^ Eicher, CW High Commands, p. 308; Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger; Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Huger.

- ^ Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Huger; Wakelyn, p. 242; Eicher, CW High Commands, p. 308; Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger; Dupuy, p. 354.

- ^ Fredriksen, p. 693; Eicher, CW High Commands, p. 308.

- ^ Eicher, CW High Commands, p. 308: Huger commanded Norfolk forces on May 21–23, 1861.

- ^ Wright, pp. 23, 53: Appointed brigadier general from South Carolina on June 17, 1861, to rank from that date, and confirmed by the Confederate Congress on August 28, 1861; promoted to major general October 7, 1861, to rank from that date, and confirmed on December 13, 1861.

- ^ Foote, pp. 226, 396; Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 165-6; Fredriksen, p. 693.

- ^ Foote, p. 231.

- ^ Garrison, p. 14; Fredriksen, pp. 140, 144, 150.

- ^ Foote, p. 444; Fredriksen, p. 694.

- ^ a b Fredriksen, p. 694.

- ^ Wert, p. 116; Eicher, CW High Commands, p. 808: Both Huger and Longstreet were promoted to major general on October 7, 1861, but Huger's name was higher on the promotions list (line rank of 8th compared to Longstreet's 9th) as prepared by Jefferson Davis.

- ^ Fredriksen, p. 694; Wert, pp. 116-24; Foote, p. 446.

- ^ Wert, pp. 124-25.

- ^ Wert, p. 125.

- ^ Foote, p. 470.

- ^ Foote, p. 477.

- ^ Winkler, pp. 83-5; Foote, pp. 498, 502-03; Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 291-2.

- ^ Time-Life, pp. 55-56.

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 295-6; Foote, pp. 510-4; Winkler, pp. 86-8.

- ^ Time-Life, pp. 68-71.

- ^ a b c Warner, p. 144.

- ^ Dupuy, p. 354; Fredriksen, p. 694; Wakelyn, p. 242.

- ^ Wakelyn, p. 242; Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Huger

References[edit]

- Alexander, Edward P. Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8078-4722-4.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

- Editors of Time-Life Books. Lee Takes Command: From Seven Days to Second Bull Run. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1984. ISBN 0-8094-4804-1.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 1, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Fredriksen, John C. Civil War Almanac. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8160-7554-6.

- Garrison, Webb. Strange Battles of the Civil War. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2001. ISBN 1-58182-226-X.

- Wakelyn, Jon L. Biographical Dictionary of the Confederacy. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8371-6124-X.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 0-671-70921-6.

- Winkler, H. Donald. Civil War Goats and Scapegoats. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2008. ISBN 1-58182-631-1.

- Wright, Marcus J., General Officers of the Confederate Army: Officers of the Executive Departments of the Confederate States, Members of the Confederate Congress by States. Mattituck, NY: J. M. Carroll & Co., 1983. ISBN 0-8488-0009-5. First published in 1911 by Neale Publishing Co.

- aztecclub.com Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Huger.

- ricehope.com Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger.

Further reading[edit]

- Rhoades, Jeffrey L. Scapegoat General: The Story of General Benjamin Huger, C.S.A. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1985. ISBN 0-208-02069-1.

- Sauers, Richard. "The Confederate Congress and the Loss of Roanoke Island." Civil War History 40, No. 2, 1994, 134–50.

External links[edit]

- "Benjamin Huger". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- historycentral.com History Central site biography of Huger.

- 1805 births

- 1877 deaths

- Military personnel from Charleston, South Carolina

- Confederate States Army major generals

- People of South Carolina in the American Civil War

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- Members of the Aztec Club of 1847

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Burials at Green Mount Cemetery