Alfred Nobel

Alfred Nobel | |

|---|---|

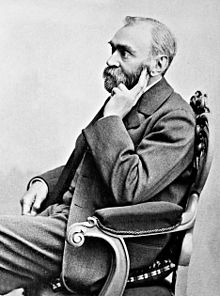

Nobel in 1896 | |

| Born | 21 October 1833 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Died | 10 December 1896 (aged 63) |

| Resting place | Norra begravningsplatsen, Stockholm 59°21′24.52″N 18°1′9.43″E / 59.3568111°N 18.0192861°E |

| Monuments | Nobel Monument |

| Occupation(s) | Chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman |

| Known for | Benefactor of the Nobel Prize, inventor of dynamite |

| Parent(s) | Immanuel Nobel Andriette Nobel |

| Relatives | Ludvig Nobel Emil Oskar Nobel Robert Nobel |

| Signature | |

Alfred Bernhard Nobel (/noʊˈbɛl/ noh-BEL, Swedish: [ˈǎlfrɛd nʊˈbɛlː] ⓘ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedish chemist, inventor, engineer and businessman. He is known for inventing dynamite as well as having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel Prize. He also made several important contributions to science, holding 355 patents in his lifetime.

Nobel displayed an early aptitude for science and learning, particularly in chemistry and languages; he became fluent in six languages and filed his first patent at the age of 24. He embarked on many business ventures with his family, most notably owning the company Bofors, which was an iron and steel producer that he had developed into a major manufacturer of cannons and other armaments. Nobel's most famous invention, dynamite, was an explosive using nitroglycerin that was patented in 1867.

Nobel was later inspired to donate his fortune to the Nobel Prize institution, which would annually recognize those who "conferred the greatest benefit to humankind".[1][2] The synthetic element nobelium was named after him,[3] and his name and legacy also survives in companies such as Dynamit Nobel and AkzoNobel, which descend from mergers with companies he founded. Nobel was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which, pursuant to his will, would be responsible for choosing the Nobel laureates in physics and in chemistry.

Personal life[edit]

Early life and education[edit]

|

Alfred Nobel was born in Stockholm, Sweden on 21 October 1833. He was the third son of Immanuel Nobel (1801–1872), an inventor and engineer, and Karolina Andriette Nobel (née Ahlsell 1805–1889).[4][5] The couple married in 1827 and had eight children. The family was impoverished and only Alfred and his three brothers survived beyond childhood.[4][6] Through his father, Alfred Nobel was a descendant of the Swedish scientist Olaus Rudbeck (1630–1702),[7] and in turn, the boy was interested in engineering, particularly explosives, learning the basic principles from his father at a young age. Alfred Nobel's interest in technology was inherited from his father, an alumnus of Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.[8]

Following various business failures caused by the loss of some barges of building material, Immanuel Nobel was forced into bankruptcy, Nobel's father moved to Saint Petersburg, Russia, and grew successful there as a manufacturer of machine tools and explosives.[9] He invented the veneer lathe (which made possible the production of modern plywood[10]) and started work on the torpedo.[11] In 1842,[12] the family joined him in the city. Now prosperous, his parents were able to send Nobel to private tutors, and the boy excelled in his studies, particularly in chemistry and languages, achieving fluency in English, French, German, and Russian.[4] For 18 months, from 1841 to 1842, Nobel went to the only school he ever attended as a child, in Stockholm.[6]

Nobel gained proficiency in Swedish, French, Russian, English, German, and Italian. He also developed sufficient literary skill to write poetry in English. His Nemesis is a prose tragedy in four acts about the Italian noblewoman Beatrice Cenci. It was printed while he was dying, but the entire stock was destroyed immediately after his death except for three copies, being regarded as scandalous and blasphemous. It was published in Sweden in 2003 and has been translated into Slovenian, French, Italian, and Spanish.[13]

Religion[edit]

Nobel was Lutheran and regularly attended the Church of Sweden Abroad during his Paris years, led by pastor Nathan Söderblom who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1930.[14][15] He was an agnostic in youth and became an atheist later in life, though he still donated generously to the Church.[16][17][18]

Relationships[edit]

Nobel traveled for much of his business life, maintaining companies in Europe and America while keeping a home in Paris from 1873 to 1891.[6] He remained a solitary character, given to periods of depression.[4][19] He remained unmarried,[5] although his biographers note that he had at least three loves, the first in Russia with a girl named Alexandra who rejected his proposal. In 1876, Austro-Bohemian Countess Bertha Kinsky became his secretary, but she left him after a brief stay to marry her previous lover Baron Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner. Her contact with Nobel was brief, yet she corresponded with him until his death in 1896, and probably influenced his decision to include a peace prize in his will.[20] She was awarded the 1905 Nobel Peace prize "for her sincere peace activities".[21] Nobel's longest-lasting relationship was with Sofija Hess from Celje whom he met in 1876 in Baden near Vienna, where she worked as an employee in a flower shop.[22][23][6] The liaison lasted for 18 years.[6][24]

Residences[edit]

In the years of 1865 to 1873, Alfred Nobel had his home in Krümmel, that now lies in the municipality of Geesthacht, near Hamburg, he afterward moved to a house in the Avenue Malakoff in Paris that same year.[25]

In 1894, when he acquired Bofors-Gullspång, the Björkborn Manor was included,[26] he stayed at his manor house in Sweden during the summers.[25] The manor house became his very last residence in Sweden and has after his death functioned as a museum.[27]

Alfred Nobel died on 10 December 1896, in Sanremo, Italy, at his very last residence, Villa Nobel, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea.[28][29]

Scientific career[edit]

As a young man, Nobel studied with chemist Nikolai Zinin; then, in 1850, went to Paris to further the work. There he met Ascanio Sobrero, who had invented nitroglycerin three years before. Sobrero strongly opposed the use of nitroglycerin because it was unpredictable, exploding when subjected to variable heat or pressure. But Nobel became interested in finding a way to control and use nitroglycerin as a commercially usable explosive; it had much more power than gunpowder. In 1851 at age 18, he went to the United States for one year to study,[30] working for a short period under Swedish-American inventor John Ericsson, who designed the American Civil War ironclad, USS Monitor. Nobel filed his first patent, an English patent for a gas meter, in 1857, while his first Swedish patent, which he received in 1863, was on "ways to prepare gunpowder".[6][31][4][32]

The family factory produced armaments for the Crimean War (1853–1856), but had difficulty switching back to regular domestic production when the fighting ended and they filed for bankruptcy.[4] In 1859, Nobel's father left his factory in the care of the second son, Ludvig Nobel (1831–1888), who greatly improved the business. Nobel and his parents returned to Sweden from Russia and Nobel devoted himself to the study of explosives, and especially to the safe manufacture and use of nitroglycerin. Nobel invented a detonator in 1863, and in 1865 designed the blasting cap.[4]

On 3 September 1864, a shed used for preparation of nitroglycerin exploded at the factory in Heleneborg, Stockholm, Sweden, killing five people, including Nobel's younger brother Emil.[6] Fazed by the accident, Nobel founded the company Nitroglycerin AB in Vinterviken so that he could continue to work in a more isolated area.[33] Nobel invented dynamite in 1867, a substance easier and safer to handle than the more unstable nitroglycerin. Dynamite was patented in the US and the UK and was used extensively in mining and the building of transport networks internationally.[4] In 1875, Nobel invented gelignite, more stable and powerful than dynamite, and in 1887, patented ballistite, a predecessor of cordite.[4]

Nobel was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1884, the same institution that would later select laureates for two of the Nobel prizes, and he received an honorary doctorate from Uppsala University in 1893. Nobel's brothers Ludvig and Robert founded the oil company Branobel and became hugely rich in their own right. Nobel invested in these and amassed great wealth through the development of these new oil regions. It operated mainly in Baku, Azerbaijan, but also in Cheleken, Turkmenistan. During his life, Nobel was issued 355 patents internationally, and by his death, his business had established more than 90 armaments factories, despite his apparently pacifist character.[4][34]

Inventions[edit]

Nobel found that when nitroglycerin was incorporated in an absorbent inert substance like kieselguhr (diatomaceous earth) it became safer and more convenient to handle, and this mixture he patented in 1867 as "dynamite".[35] Nobel demonstrated his explosive for the first time that year, at a quarry in Redhill, Surrey, England. In order to help reestablish his name and improve the image of his business from the earlier controversies associated with dangerous explosives, Nobel had also considered naming the highly powerful substance "Nobel's Safety Powder", but settled with Dynamite instead, referring to the Greek word for "power" (δύναμις).[36][37]

Nobel later combined nitroglycerin with various nitrocellulose compounds, similar to collodion, but settled on a more efficient recipe combining another nitrate explosive, and obtained a transparent, jelly-like substance, which was a more powerful explosive than dynamite. Gelignite, or blasting gelatin, as it was named, was patented in 1876; and was followed by a host of similar combinations, modified by the addition of potassium nitrate and various other substances.[35] Gelignite was more stable, transportable and conveniently formed to fit into bored holes, like those used in drilling and mining, than the previously used compounds. It was adopted as the standard technology for mining in the "Age of Engineering", bringing Nobel a great amount of financial success, though at a cost to his health. An offshoot of this research resulted in Nobel's invention of ballistite, the precursor of many modern smokeless powder explosives and still used as a rocket propellant.[38]

Nobel Prize[edit]

There is a well known story about the origin of the Nobel Prize, although historians have been unable to verify it and some dismiss the story as a myth.[39] In 1888, the death of his brother Ludvig supposedly caused several newspapers to publish obituaries of Alfred in error. One French newspaper condemned him for his invention of military explosives—in many versions of the story, dynamite is quoted, although this was mainly used for civilian applications—and this is said to have brought about his decision to leave a better legacy after his death.[4][40] The obituary stated, Le marchand de la mort est mort ("The merchant of death is dead"),[4] and went on to say, "Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday."[41] Nobel read the obituary and was appalled at the idea that he would be remembered in this way. His decision to posthumously donate the majority of his wealth to found the Nobel Prize has been credited to him wanting to leave behind a better legacy.[42][4] However, it has been questioned whether or not the obituary in question actually existed.[42]

On 27 November 1895, at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, Nobel signed his last will and testament and set aside the bulk of his estate to establish the Nobel Prizes, to be awarded annually without distinction of nationality.[35][43] After taxes and bequests to individuals, Nobel's will allocated 94% of his total assets, 31,225,000 Swedish kronor, to establish the five Nobel Prizes. This converted to £1,687,837 (GBP) at the time.[44][45][46][47] In 2012, the capital was worth around SEK 3.1 billion (US$472 million, EUR 337 million), which is almost twice the amount of the initial capital, taking inflation into account.[45]

The first three of these prizes are awarded for eminence in physical science, in chemistry and in medical science or physiology; the fourth is for literary work "in an ideal direction" and the fifth prize is to be given to the person or society that renders the greatest service to the cause of international fraternity, in the suppression or reduction of standing armies, or in the establishment or furtherance of peace congresses.[35]

The formulation for the literary prize being given for a work "in an ideal direction" (i idealisk riktning in Swedish), is cryptic and has caused much confusion. For many years, the Swedish Academy interpreted "ideal" as "idealistic" (idealistisk) and used it as a reason not to give the prize to important but less romantic authors, such as Henrik Ibsen and Leo Tolstoy. This interpretation has since been revised, and the prize has been awarded to, for example, Dario Fo and José Saramago, who do not belong to the camp of literary idealism.[48]

There was room for interpretation by the bodies he had named for deciding on the physical sciences and chemistry prizes, given that he had not consulted them before making the will. In his one-page testament, he stipulated that the money go to discoveries or inventions in the physical sciences and to discoveries or improvements in chemistry. He had opened the door to technological awards, but had not left instructions on how to deal with the distinction between science and technology. Since the deciding bodies he had chosen were more concerned with the former, the prizes went to scientists more often than engineers, technicians or other inventors.[49]

Sweden's central bank Sveriges Riksbank celebrated its 300th anniversary in 1968 by donating a large sum of money to the Nobel Foundation to be used to set up a sixth prize in the field of economics in honor of Alfred Nobel. In 2001, Alfred Nobel's great-great-nephew, Peter Nobel (born 1931), asked the Bank of Sweden to differentiate its award to economists given "in Alfred Nobel's memory" from the five other awards. This request added to the controversy over whether the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel is actually a legitimate "Nobel Prize".[50]

Death[edit]

Nobel was accused of high treason against France for selling Ballistite to Italy, so he moved from Paris to Sanremo, Italy, in 1891.[51][52] On 10 December 1896, he suffered a stroke and was partially paralyzed to where he could speak only his native tongue. Nobel was surrounded by his paid servants at the time of his death who did not speak his native tongue so he wrote, "how sad it is to be without a friend who could whisper a consoling word and would one day gently close one's eyes."[53] He had left most of his wealth in trust, unbeknownst to his family, in order to fund the Nobel Prize awards.[4] He is buried in Norra begravningsplatsen in Stockholm.[54]

Monuments and legacy[edit]

The Monument to Alfred Nobel (Russian: Памятник Альфреду Нобелю, 59°57′39″N 30°20′06″E / 59.960787°N 30.334905°E) in Saint Petersburg is located along the Bolshaya Nevka River on Petrogradskaya Embankment. It was dedicated in 1991 to mark the 90th anniversary of the first Nobel Prize presentation. Diplomat Thomas Bertelman and Professor Arkady Melua were initiators of the creation of the monument (1989). Professor A. Melua has provided funds for the establishment of the monument (J.S.Co. "Humanistica", 1990–1991). The abstract metal sculpture was designed by local artists Sergey Alipov and Pavel Shevchenko, and appears to be an explosion or branches of a tree.[55] Petrogradskaya Embankment is the street where Nobel's family lived until 1859.[56] Criticism of Nobel focuses on his leading role in weapons manufacturing and sales, and some question his motives in creating his prizes, suggesting they are intended to improve his reputation.[57][58]

References[edit]

- ^ "Alfred Nobel's Fortune". The Norwegian Nobel Committee. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel's Will". The Norwegian Nobel Committee. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Nobelium". Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Alfred Nobel". Britannica.com. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Alfred Nobel's life and work". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Encyclopedia of Modern Europe: Europe 1789–1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire, "Alfred Nobel", 2006 Thomson Gale.

- ^ Schück, Henrik, Ragnar Sohlman, Anders Österling, Carl Gustaf Bernhard, the Nobel Foundation and Wilhelm Odelberg, eds. Nobel: The Man and His Prizes. 1950. 3rd ed. Coordinating Ed., Wilhelm Odelberg. New York: American Elsevier Publishing Company, Inc., 1972, p. 14. ISBN 0-444-00117-4, ISBN 978-0-444-00117-7. (Originally published in Swedish as Nobelprisen 50 år: forskare, diktare, fredskämpar.)

- ^ "A Tribute to the memory of Alfred Nobel" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel – his life and work". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ "Nobel Plywood". Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "The Man Who Made It Happen — Alfred Nobel". 3833. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel". NE (in Swedish). 1 July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Alfred Nobel (2008). Némésis: tragédie en quatre actes. Belles lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-44342-3.

- ^ "Nobel of Peace Laureates". March 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

– For seven years, from 1894 to 1901, Söderblom preached in Paris, where his congregation included Alfred Nobel

- ^ "Alfred Nobel, hans far och hans bröder". March 2013. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

(swe: Genom dop och konfirmation var Alfred Nobel lutheran -en: Alfred Nobel was through baptism and confirmation a Lutheran)

- ^ "Alfred Nobel – St. Petersburg, 1842–1863". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Michael Evlanoff; Marjorie Fluor (1969). Alfred Nobel, the loneliest millionaire. W. Ritchie Press. p. 88. "He declared himself an agnostic in his youth, an atheist later, but at the same time, bestowed generous sums to the church..."

- ^ Cobb, Cathy, and Harold Goldwhite. Creations of Fire: Chemistry's Lively History from Alchemy to the Atomic Age. New York: Plenum, 1995. Print. "But Nobel, both atheist and a socialist..."

- ^ "Alfred Nobel | Biography & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Nobel Media AB (16 June 2021). "Bertha von Suttner—Biographical". nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1905". nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Sofie Hess in Wien Geschichte Wiki". wienbibliothek.at (in German). Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Širokogrudni Alfred Nobel in njegova razsipna celjska ljubezen Sofija Hess" [Broad-minded Alfred Nobel and his wasteful Celje love Sofia Hess] (in Slovenian). celje.info. 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Skok, Blaž: Kako se je Alfred Nobel zaljubil v “požiralko bankovcev” iz Celja Archived 3 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine [How Alfred Nobel fell in love with a "banknote devourer" from Celje] (in Slovenian). N1 Slovenija, Ljubljana 2023.

- ^ a b "Alfred Nobel – Alfred Nobels Björkborn" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Björkborn Manor". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Björkborn Manor – Alfred Nobels Björkborn" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel's final years in Sanremo". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel – en mångsidig man" (PDF). The Nobel Prize (in Swedish). December 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ "Alfred B Nobel – Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon". sok.riksarkivet.se. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney (2004). Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries Archived 1 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p. 256. John Wiley & Songs, Inc., New Jersey. ISBN 0-471-24410-4.

- ^ "Patents – Alfred Nobel". nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel – Dynamit" (in Swedish). Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel (1833–1896)". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Nobel, Alfred Bernhard". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 723–724.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel - Dynamit". Tekniska museet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel | Biography, Inventions, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Definition of ballistite | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Andrews, Evan (23 July 2020). "Did a Premature Obituary Inspire the Nobel Prize?". Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ The History Channel, Modern Marvels, episode 038 (originally aired 21 June 1999)

- ^ Golden, Frederic (16 October 2000). "The Worst and the Brightest". Time. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007.

- ^ a b Schultz, Colin (9 October 2013). "Blame Sloppy Journalism for the Nobel Prizes". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel's will". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ At exchange rate of 18.5:1 in SEK:GBP

- ^ a b Lobell, Håkan (2010). Historical Monetary and Financial Statistics for Sweden Exchange rates, prices, and wages, 1277–2008. S V E R I G E S R I K S B A N K. p. 291. ISBN 978-91-7092-124-7.

- ^ Abrams, Irwin (2001). The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates. Watson Publishing International. p. 7. ISBN 0-88135-388-4.

- ^ Fant, Kenne (Ruuth, Marianne, transl.) (1991). Alfred Nobel: a biography. New York: Arcade Publishing ISBN 1-55970-328-8, p. 327

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize", Northern Light, Renaissance Books, pp. 59–61, 30 April 2019, doi:10.2307/j.ctvzgb63g.13, ISBN 978-1-898823-91-9, S2CID 243214222, retrieved 20 May 2021

- ^ Hervey, Dr Angus (4 October 2017). "Why is there no Nobel Prize in technology?". Quartz. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ (Ntb-Afp). "Alfred Nobels familie tar avstand fra økonomiprisen". Aftenposten.no. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Nobel, Alfred. "Alfred Nobel's House in Paris". Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Nobel, Alfred. "Alfred Nobel's Final Years in Sanremo". Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Alfred Nobel" (PDF). Vanderbilt University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ He, Tianlin (5 November 2017), A visit to Alfred Nobel on All Saints' Day, archived from the original on 7 May 2021, retrieved 5 January 2021

- ^ "Monument to Alfred Nobel". Saint-Petersburg.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Lemmel, Birgitta. "Alfred Nobel – St. Petersburg, 1842–1863". Nobel Media AB. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ How ‘merchant of death’ Alfred Nobel became a champion of peace Archived 28 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine in The Local 4 October 2010

- ^ Article Archived 14 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine by Kenne Fant in Svenska Dagbladet 10 December 2002

Further reading[edit]

- Schück, H, and Sohlman, R., (1929). The Life of Alfred Nobel, transl. Brian Lunn, London: William Heineman Ltd.

- Alfred Nobel US Patent No 78,317, dated 26 May 1868

- Evlanoff, M. and Fluor, M. Alfred Nobel – The Loneliest Millionaire. Los Angeles, Ward Ritchie Press, 1969.

- Sohlman, R. The Legacy of Alfred Nobel, transl. Schubert E. London: The Bodley Head, 1983 (Swedish original, Ett Testamente, published in 1950).

- Jorpes, J. E. (1959). "Alfred Nobel". BMJ. 1 (5113): 1–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5113.1. PMC 1992347. PMID 13608066.

External links[edit]

- Alfred Nobel – Man behind the Prizes

- Biography at the Norwegian Nobel Institute

- "The man behind the prize - Alfred Nobel" (Nobelprize.org)

- Documents of Life and Activity of The Nobel Family. Under the editorship of Professor Arkady Melua. Series of books. (mostly in Russian)

- "The Nobels in Baku" in Azerbaijan International, Vol 10.2 (Summer 2002), 56–59.

- Newspaper clippings about Alfred Nobel in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Works by or about Alfred Nobel at Internet Archive

- Alfred Nobel and his unknown coworker

- Alfred Nobel

- 1833 births

- 1896 deaths

- Burials at Norra begravningsplatsen

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Nobel family

- Nobel Prize

- Engineers from Stockholm

- 19th-century Swedish businesspeople

- 19th-century Swedish scientists

- 19th-century Swedish engineers

- 19th-century Swedish chemists

- 19th-century Swedish philanthropists

- Explosives engineers

- Bofors people