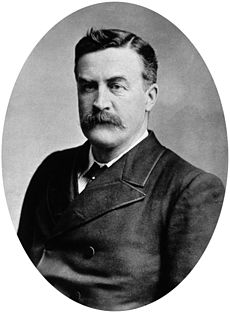

Alexander Ogston

Alexander Ogston | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 19, 1844 |

| Died | February 1, 1929 (aged 84)[2] |

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen |

| Known for | The discovery of Staphylococcus aureus |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Jane Hargrave (1867–1873) Isabella Margaret Matthews[3] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Surgery/Bacteriology |

| Institutions | Aberdeen Royal Infirmary |

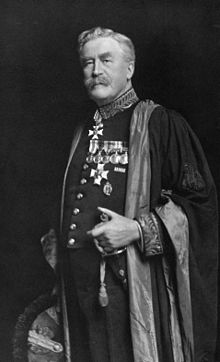

Sir Alexander Ogston KCVO MD CM LLD (19 April 1844 – 1 February 1929) was a British surgeon, famous for his discovery of Staphylococcus.

Life[edit]

Ogston was the eldest son of Amelia Cadenhead and her husband Prof. Francis Ogston (1803–1887), Professor of Medical Jurisprudence at the University of Aberdeen.[4] He had a brother who was also a professor.

University of Aberdeen[edit]

Ogston began his medical training at Marischal College in 1862 and graduated as Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery at the recently united University of Aberdeen in 1865 with honours in medicine and surgery at the age of 21. [5] He obtained his MD a year later in 1866. He was appointed as a full surgeon to the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary in 1874.[5] He was Assistant Professor of Medical Jurisprudence and Materia Medica, Lecturer in Ophthalmology and Anaesthetist before being appointed as Regius Professor of Surgery in 1882.[6] He is credited with the introduction of carbolic spray to Aberdeen.[7]

Staphylococcus[edit]

Ogston was reported to have called on Joseph Lister and rigorously followed his antiseptic principles.[5] These are aptly phrased in a small ditty composed by his students.

The spray, the spray, the antiseptic spray

A.O. would shower it morning, night and day

For every sort of scratch

Where others would attach

A sticking plaster patch

He gave the spray.[5]

Ogston followed the work of other contemporaries such as Koch, J.C. Ewart from Edinburgh (published on different types of bacteria), and Kohler from Berne (who found bacteria in cases of osteomyelitis and 'strumitis'.[5]

Following his examination of the organisms from the abscess of James Davidson, Ogston used the shed behind his house as a laboratory (receiving a grant (£50) from the British Medical Association (BMA), with which he purchased a Zeiss microscope and the methyl-aniline dye used by Koch) to continue his research.

Following Kochs postulates and staining methods, Ogston set about isolating the causative organism of Davidson's wound.[5] By experiment Ogston concluded that the optimal conditions for cultivation of this organism were hen's egg medium grown in small bottles shielded from contamination by glass 'shades.[5] Using samples from 82 abscesses, Ogston successfully isolated bacteria from 65 samples, the others being referred to as "cold". He was then able to transfer pure colonies to guinea-pigs, white mice or wild mice.[5]

Ogston soon realised there were '"two forms of micrococcus: one in the form of chains or necklaces to which the name 'streptococcus' had been given and produced the more violent inflammation, and the other growing in masses or clusters [like the roe of a fish], to which I gave the name 'staphylococcus' which cause a less violent inflammatory disease'.[5] He also noted that a transferring a 1/146 016 000 dilution of the original pus sample could induce abscesses in new subjects.[5] Ogston demonstrated that these bacteria could be killed by heat or carbolic acid, fulfilling Kochs postulates.[5] He also noted that " micrococci so deleterious when injected" were seemingly "harmless on the surface of wounds and ulcers".[5] An observation of the existence of some staphylococci as part of the normal flora.[5]

Ogston encountered a great deal of difficulty convincing the medical establishment of his observations on Staphylococcus.[5] The Aberdeen branch of the BMA, received his findings with disbelief.[5] The editor of the British Medical Journal stated at the time 'can anything good come out of Aberdeen'.[5] After a careful study of the evidence presented by Ogston, his contemporary, Joseph Lister agreed with his findings however, another peer, Watson Cheyne was still sceptical.[5] Given this local skeptisim, Ogston decided to present his discoveries to a surgical congress in Berlin where he had previously presented a paper "genu valgum" on 9 April 1880.[5] Ogston delivered this presentation on abscesses in German which was then published. He was subsequently made a 'Fellow' of the German Surgical Society despite his youth (36 years old).[5] The next year Ogston published his observations in the British Medical Journal.[5] After this point his papers were refused, and instead he published in the Journal of Anatomy and Physiology.[5]

Military career[edit]

Ogston served in the 1884 Egyptian War and the Boer War. He was also instrumental in arguing for the creation of the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1898. During the First World War when over seventy years old, he was sent to assist with the management of severe trauma.[8]

Private life[edit]

Ogston married twice. He had three children with his first wife Mary Jane Molly Ogston (née Hargrave). They were Mary Letitia, Francis, Flora and Walter Henry. His wife died in 1873 and he later remarried and they had five children, Alfred James, Douglas John, Helen Charlotte Elizabeth, Constance Amelia Irene, Rose, Alexander and Ranald Frederick.[9] Both Helen and Constance were active suffragettes.

Royal acknowledgement[edit]

In 1892, Queen Victoria appointed him Surgeon in Ordinary, a post he also held under King Edward VII and King George V. He was appointed Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 1912.

Legacy[edit]

The Surgical Society of the University of Aberdeen is named the "Ogston Society" in his honour.[10] The University Department of Surgery also awards an annual prize in his honour to the best student in surgery.[11]

References[edit]

- ^ Smith, G. (1965). "Alexander Ogston (1844–1929)". British Journal of Surgery. 52 (12): 917–920. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800521203. PMID 5322135. S2CID 36468839.

- ^ "The Death of Sir Alexander Ogston". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 20 (4): 412. 1929. PMC 1710619. PMID 20317303.

- ^ "Sir Alexander Ogston, K.c.v.o., M.d., C.m., Ll.d". BMJ. 1 (3554): 325–327. 1929. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3554.325. PMC 2450191. PMID 20774478.

- ^ Johnston, William (1899). Some account of the last bajans of King's and Marischal Colleges, MDCCCLIX-LX: and of those who joined their class in the University of Aberdeen during the semi, tertian and magistrand sessions MDCCCLX-LXIII. Privately printed by Her Majesty's Printers at the Adelphi Press. p. 42. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Newsom S. W. (December 2008). "Ogston's coccus". J. Hosp. Infect. 70 (4): 368–372. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2008.10.001. PMID 18952323. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Lyell, A. (1989). "Alexander Ogston, micrococci, and Joseph Lister". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 20 (2): 302–310. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70035-9. PMID 2644319.

- ^ Pennington, T. H. (1988). "The Lister steam spray in Aberdeen". Scottish Medical Journal. 33 (1): 217–218. doi:10.1177/003693308803300115. PMID 3291113. S2CID 40018012.

- ^ Adam, A. (1998). "Alexander Ogston and the Army Medical Services formation of the Royal Army Medical Corps 1 July 1898". Scottish Medical Journal. 43 (5): 156–157. doi:10.1177/003693309804300512. PMID 9854306. S2CID 37199920.

- ^ "Ogston, A". www.scotlandswar.co.uk. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Sir Alexander Ogston". Ogston Society.

- ^ "Endowed Prizes and Medals". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.