George Leybourne

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

George Leybourne | |

|---|---|

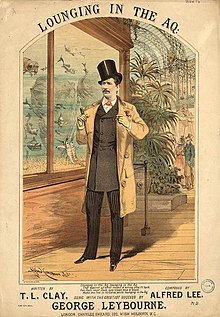

Lounging in the Aq (Royal Aquarium), sheet music cover by Alfred Concanen (1880) | |

| Born | Joseph Saunders 17 March 1842 Gateshead, County Durham, England |

| Died | 15 September 1884 (aged 42) Islington, London, England |

| Other names | Joe Saunders, Champagne Charlie |

| Occupation(s) | Music hall singer, songwriter |

George Leybourne (17 March 1842 – 15 September 1884) was a singer and Lion comique style entertainer in British music halls during the 19th century who, for much of his career, was known by the title of one of his songs, "Champagne Charlie". Another of his songs, and one that can still be heard, is "The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze". He remains among the best known 19th century music hall performers.

Early life[edit]

George Leybourne was born Joseph Saunders in Gateshead; however, at an early age he and his family relocated to London. Before he worked for music halls he worked as an engineer in, amongst other places, South West England.[1] For his early music hall performances in the Northern England, including Liverpool and Newcastle he used his real name - Joe Saunders - a fact which, in the past, caused much confusion as to his real name. His first performance documented in London using the stage-name George Leybourne was at the Bedford Music Hall in 1863, but it is known that he had performed in some of the smaller East-End venues in the months before this.[2]

Career[edit]

In 1866 with composer Alfred Lee, he wrote the song "Champagne Charlie", premiering it in Leeds during August of that year. It took several months before it became successful. Another of Leybourne's major song successes, also dating from 1866, was "The Flying Trapeze", music by Alfred Lee. The song represented a fascination with trapeze artistes then performing in the UK, including Jules Léotard who had appeared in the Alhambra Music Hall in London. In 1867 it was published in the United States by C. H. Ditson & Co, with music attributed to Gaston Lyle.

During the 1860s, Leybourne, along with several contemporaries including Arthur Lloyd and Alfred Peck Stevens developed a new type of music hall character, the Lion Comique; a dandy or attractive, fashionable, young man. For this style, performers relied less on copying burlesque, and instead sought inspiration in their everyday experiences and the characters of daily street life. Audiences loved to join in the chorus and "give the bird".[3] In some of his songs he appeared immaculately dressed in white tie and tails, when he would declare his love for the high life, women, and champagne. However, he also earned a reputation for his many character songs, which were detailed studies of people of various classes.

In 1868, when William Holland became manager of the Canterbury Music Hall, he employed Leybourne with an exclusive contract of £25 a week, providing him with a carriage drawn by four white horses. During the next year by performing, with Holland's permission, in several other halls additionally, his salary increased to £120 per week.

Leybourne also wrote the lyrics to the 1871 song "If Ever I Cease to Love", some of the lyrics of which caused a scandal. It is often remembered presently for its association with Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

The song was sung by Lydia Thompson, for the burlesque adaptation of Jacques Offenbach's operetta Bluebeard, with which she was touring the United States. When he visited New Orleans in 1872, Russian Grand Duke Alexei Romanov saw Bluebeard and was fascinated by both the singer and the song.

When Jenny Hill performed at the London Pavilion, she stopped the show, requiring Leybourne to wait for her act to finish, after which he carried her back for an encore.

Leybourne and Alfred Vance, also known as The Great Vance, have historically been considered as rivals in popular culture, an understanding elaborated by the 1944 movie Champagne Charlie. Latest research shows that while they both sang songs extolling the virtues of various alcoholic drinks, their careers were somewhat different. Leybourne concentrated on his music hall performances, while Vance entertained middle-class audiences with 'safe' concert party shows. It was in their advertisements that the rivalry seemed evident. For the movie Champagne Charlie Leybourne was played by comedian Tommy Trinder, while Alfred Vance was played by Stanley Holloway.

Death and legacy[edit]

During a career spanning 23 years Leybourne sang more than 200 songs; however, towards the end of his career he failed to adapt to the changing times and his popularity decreased. He died impoverished in England in Islington, aged 42.

Leybourne is buried at Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, London with his actress daughter Florence Leybourne, her husband, the music hall performer Albert Chevalier and grandson Frederick. His headstone, with the epitaph "God's finger touched him and he slept", was erected by fellow music hall entertainer Dan Leno, and the Grand Order of Water Rats. George Leybourne's grave is cared for by The Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America.

Leybourne appeared at Wilton's Music Hall in London's East End, the world's oldest surviving grand music hall, and an adjoining modern residential apartment block has been named "George Leybourne House" after him.

On 29 July 1970 a blue plaque commemorating Leybourne was erected by the Greater London Council ("GLC") at the instigation of the British Music Hall Society and was unveiled by Don Ross at Leybourne's former home at 136 Englefield Road, Islington.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ Banham, M., The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 642

- ^ Beeching, Christopher. The Heaviest of Swells, DCG Publications, 2011; Banham, M., The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 768

- ^ Banham, M., The Cambridge Guide to Theatre, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 768

- ^ Ashton, Ellis (16 July 1970). "Music Hall Miscellany". The Stage. p. 9.